The oldest news about the Ria de Muros and Noia and north coast do not allow us to speak with precision about the first inhabitants of the area. Roman sources mentioned localities and residents difficult to pinpoint.

Then called Puebla del Muro (Wall Town), it appeared in writing for the first time in 1286, when King Sancho IV granted a number of privileges to encourage fishing and related activities. This shows that, in the Middle Ages, we were one of the most important ports of Galicia, a position we would occupy for generations.

In 1298 control of the town - which was then Crown property, responsible directly to the king - passed to the Archbishop of Santiago de Compostela. From that moment it is apparent that its standing grew as a strategic port, due to commerce as well as fishing.

Muros and Noia Bay had, at that time, a treasure in the richness of its waters. The sardine would be the economic foundation of the whole area. Fishing, and the salting industry, would make Muros an exporting port with sales throughout the Iberian Peninsula. Muros sardines had a reputation, in the port of Barcelona for example.

A strategic spot attracts attention. Norman and Muslim pirates attacked the Galician coast, and Muros was a coveted target. As a result, within a few decades of taking charge of the town, the Archbishopric had built its first town wall, as shown in records from the early fourteenth century. It contained a small area, from the current Town Hall to the Collegiate church grounds and down to the shore. By the sixteenth century this first enclosure would be expanded, with new ramparts and an increasingly well-armed castle. The city’s defences extended to the neighbouring hills and in particular to the cove at Louro.

Descriptions from the late Middle Ages paint an extraordinary picture: a port with a large fleet; commercial expeditions to Flanders and the Mediterranean; major shipyards in the estuary. 1,000 citizens are chronicled at the end of the 15th century, implying as many as 5,000 inhabitants. Around that time, in 1500, Pope Alexander VI dignified the parish of Muros with Collegiate status.

Thus was born a village forever linked to the sea, especially to fishing and related industries; but also to trade, and the needs of pilgrims arriving from Europe. The Guild of Merchants, comprising much of the population (the villagers “are by and large fishermen and sea traders,” we are told in 1607) was among the most powerful in the Kingdom of Galicia.

Over the following centuries, the sea would retain its central role. The fish were a safety net for the coastal populations, which helped them survive when famine struck in the hinterland. On the other hand, the ports were often particularly afflicted by epidemics, several outbreaks occurring in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries; and Muros especially suffered. Gradually, other coastal villages overtook it. Those 1,000 residents dwindled to 600 at the beginning of the 17th century, and even fewer in the 18th.

Attacks from the sea continued to come. Several times the port suffered assault from pirates and enemy fleets. At that time it was common for the residents to flee inland for several months of the year, to escape these raids.

The sardine, however, was still a great wealth. And when it was in short supply, everything was in jeopardy. In 1694, for example, as a last resort the estuary was blessed - a plea for divine intervention after several years of poor fishing.

Yet despite this, on the verge of modern times, in 1795, Muros remained the third-biggest port in Galicia in terms of sardine catches, after Ares and Cangas, and its jurisdiction - which included Carnota, Mazaricos and Outes - the Archbishopric’s most important, after the capital. Descriptions from that time continue to highlight the size of its fishing and merchant fleet and the harbour’s military defences.

Muros came into the modern age with a tragic war episode. During the French invasion it was attacked several times. The worst was in 1809, when the invading troops entered the city to crush an attempted insurrection, resulting in the almost total destruction of the town inside the wall. Many residents fled by sea, to Porto do Son and Noia.

This episode undoubtedly impoverished a generation. The estuary, as always, came to the rescue. Fishing was its salvation; but everything was changing.

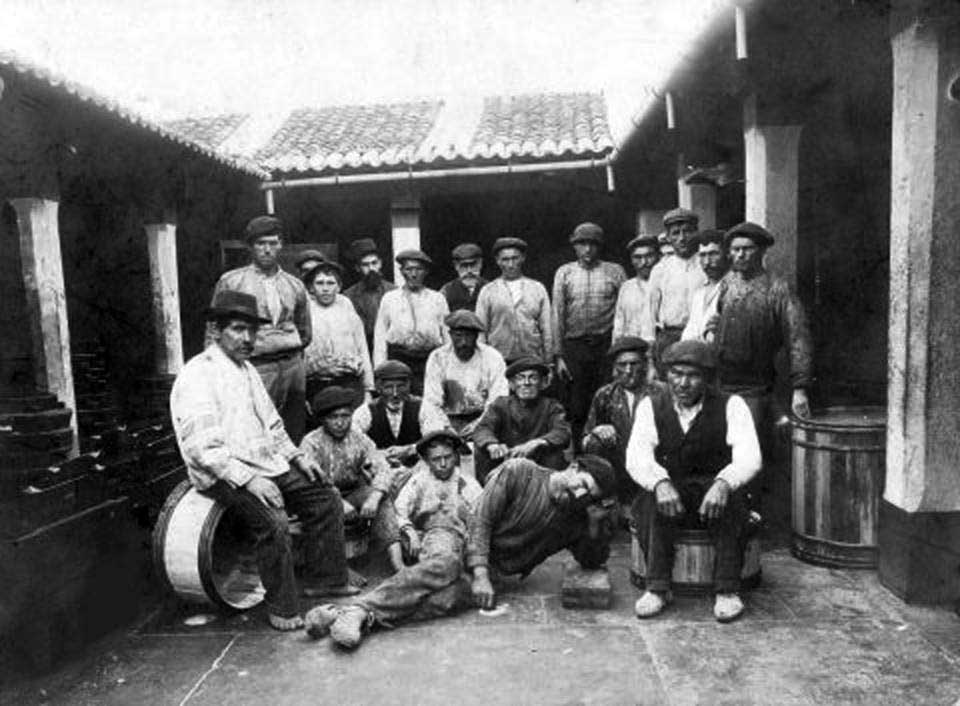

For some decades the commercial importance of the estuary had been attracting industrialists from elsewhere: Catalans, who introduced a new operating model. New techniques of salting and subsequent canning changed the traditional methods of harvesting the sea, with mixed results. On the one hand, many new factories appeared in Muros and around the estuary, leading to intense trading and frenzied activity. On the other, the new model led to the small-time fishermen being replaced by industrial fishing fleets with mariners as employees, in a process of proletarianization and impoverishment of the common man. From very early on in the eighteenth century there were complaints about the threat that large-scale industry posed to small local producers.

The overfishing, too, put the estuary under such pressure that its sardines were practically gone by the early twentieth century. Mass emigration, which until then had been a phenomenon of inland Galicia, now affected the coast and Muros. Canneries became ruins, several visible today along the coast, some of them having played the role of prison camps during the Civil War.

Since the 1960s, the market has recovered somewhat due to advances in offshore fishing. Muros will thus remain linked to the sea, its boats and its harbour.